Autopsy of a Crime Lab: Exposing the Flaws in Forensics

Brandon L. Garrett

Forensic analysis is perhaps best known through its fictional portrayals in crime novels and television courtroom dramas: A crime occurs, law enforcement gathers evidence from the scene, and a team of dedicated forensic analysts interrogate that evidence in a crime lab using cutting-edge scientific methods. Potential suspects get fingerprinted, an identifying “match” gets made with the help of government databases, and judges allow prosecutors to introduce the unbiased testimony of proven experts in the field who trot out their damning, seemingly incontrovertible forensic conclusions to an attentive jury.

Autopsy of a Crime Lab exposes some of the most common misconceptions about forensic analysis and examines their collective impact on the criminal justice system. Through detailed examinations of the forensic failures responsible for the wrongful convictions of exonerees, author Brandon L. Garrett categorizes the errors made by forensic “experts,” identifies how and why these mistakes continue to occur, and argues forcefully for a comprehensive, science-based, multi-pronged approach to restore integrity to the essential discipline of forensics. You can read more about the book, and learn how purchase it or request it for your library, at its University of California Press webpage: https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520379336/autopsy-of-a-crime-lab.

Questions for Discussion

1. Prior to reading Autopsy of a Crime Lab, what was your opinion of fingerprint evidence? How have your views changed in light of what you now know? Why might fictional portrayals of forensic analysis influence real-life perceptions of its accuracy and reliability?

2. “With the exception of nuclear DNA analysis…no forensic method has been rigorously shown to have the capacity to consistently, and with a high degree of certainty, demonstrate a connection between evidence and a specific individual or source.” (7) What implications can be drawn from this critique by the NAS of common forensic methodologies used by law enforcement? To what extent does society’s faith in the criminal justice system depend on a shaky premise—that forensic analysis of all kinds is infallible?

3. Consider the 1982 “bite mark case” in Newport News, Virginia, that resulted in a murder conviction and death sentence for Keith Allen Harward, who was incarcerated for 33 years before being exonerated by DNA analysis. How does Harward’s case expose forensic odontology as pseudoscience? Should experts whose flawed forensic analysis leads to the conviction of innocent people be held responsible for those injustices? Why or why not?

4. Unlike older forensics methods that connect evidence to individual suspects and assert questionable “matches,” DNA testing generates statistical probabilities. How does this paradigm shift undergone by forensic analysis—from its humble beginnings as an outgrowth of the law enforcement community to its reliance on cutting-edge science, math, and digital technologies—change the playing field? Why might this shift might be problematic for all parties in the criminal justice system?

5. Together with the Innocence Project co-founder Peter Neufeld, author Brandon L. Garrett discovered extensive flawed forensic testimony in cases that later resulted in DNA exonerations. If you were selected as a juror after reading Autopsy of a Crime Lab, and forensic experts testified at trial on fingerprints, firearms, bite marks, blood patterns, hair strands, or arson, how would you feel about relying on that evidence to render your verdict?

6. “What is expertise? A person should only be considered an expert if they are in fact very good at forensics work.” (96) Given all that is at stake in forensic analysis, how does the fact that some forensics jobs require no formal training affect your opinion of the discipline as a whole? To what extent do you agree with the author that forensic analysts should be required to demonstrate their reliability through regular proficiency testing?

7. Consider the hidden role of bias in forensic analysis. In your discussion, you may want to address different types of bias, including confirmation bias, adversarial bias, and context bias. How does blinding like the kind used by the Houston Forensic Crime Center work to combat these kinds of bias?

8. Discuss how improperly-run crime labs and crime scene contamination contribute to forensic analysis failures. How would you begin to address the phenomenon of so-called “bad apples” within crime lab and law enforcement personnel? Which of the many egregious failures by forensics experts examined in Autopsy of a Crime Lab left an impression on you?

9. “It should be unconstitutional to ever use black box machines, of unknown reliability, to investigate crimes, much less to convict people of crimes.” (166) How does commercial, proprietary technology of the kind used by law enforcement agencies to gather forensic evidence potentially impinge on individual rights?

10. Discuss the impact of digital databases on the field of forensics. To what extent do these databases privilege law enforcement officers over the accused? In your discussion, consider the significance of the case of Brandon Mayfield, the Oregon attorney whose fingerprint was erroneously identified by the FBI in its investigation into the 2004 Madrid train bombings. Why was that case so seminal in transforming forensic analysis?

An Interview with Brandon L. Garrett

Q: In Autopsy of a Crime Lab, you characterize your views on forensics as a young lawyer as “unformed” and recall that you assumed “most of it was good science.” To what extent do you find a similar good-faith attitude persists among lawyers, judges, and jurors today?

A: I have surveyed thousands of people eligible for jury duty around the country, and they overwhelmingly report that they think that different types of forensic evidence are unique and extremely reliable. We share a broad cultural assumption that evidence like a latent fingerprint can be identified and linked to a single person. Lawyers even worry that there is a CSI effect, and jurors will never convict a person unless there is forensic evidence. The opposite is true: people place great weight on forensic evidence and are really shocked to hear that the reliability of so much of that evidence is untested to this day.

Q: The Supreme Court’s decision in Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals Inc., put the onus on the judges to assure the validity and reliability of evidence before admitting it at trial. Given their professional commitment to administering justice, why do you think judges aren’t leading the charge to improve the overall quality control of forensic evidence?

A: Judges have failed us. They have not meaningfully acted as gatekeepers to make sure that only reliable expert evidence is used in criminal cases. Lawyers generally lack scientific literacy and for years, they simply accepted what forensic experts have said at face value. Judges are also reluctant to keep out evidence that prosecutors rely on; many come from a prosecution background themselves, and themselves remember relying on the same types of forensic evidence. The result is a deeply inaccurate and unfair system.

Q: You offer a compelling mythological alternative to blind lady justice—that of Perseus seizing the shared eye of the three Graea—and propose it as a new kind of model for the type of blinding that should be incorporated into forensic analysis to render it both more scientific and more just. Can you elaborate on this metaphor for your readers?

A: We are all biased; our expectations always affect our decision-making. Usually that is a good thing, but for forensic experts, it can cause tragic miscarriages of justice. We need our forensic experts to work like scientists, without biasing information, like the defendant’s race or criminal record. We can do that by blinding them: by giving them only the information they need to do their forensic analyses and nothing more.

Q: If a single ethical code for practicing forensic analysts were to be established in the United States, how do you envision its enforcement? What level of responsibility do professional associations like the American Board of Criminalists (ABC) and American Academy of Forensic Sciences (AAFS) assume currently in the event of unethical testimony by one of their members?

A: We need forensic crime labs and professional organizations to review how forensic examiners actually do their work and testify in court. More labs, fortunately, are starting to see that as part of their job, but they need binding ethical standards. In the past, when forensic experts testified in ways that were overstated, unscientific, and outright fabricated, they suffered no professional consequence whatsoever. That must stop.

Q: Why are some in the law enforcement community resistant to the creation of a National Institute of Forensic Science modeled after the National Institutes of Health, as proposed by the landmark 2009 report on forensics by the National Academy of Sciences? Given the many cases of faulty forensic analysis documented and overturned by organizations like the Innocence Project that have resulted in exonerations and significant financial settlements, why hasn’t more been done by the government to prevent these catastrophes from happening?

A: Creating a new federal agency is no small request but the scientific community did not lightly call for a National Institute of Forensic Science. They felt that it was crucial. Forensics should be regulated, just like air travel and pharmaceuticals. Crime labs need to be regulated like our clinical laboratories have long been. The only explanation for the difference is that as a society we care less about the tests done in criminal cases than the tests done by doctors.

Q: How have your private encounters with exonerees who have been victims of faulty forensics affected you?

A: I decided to become a law professor because of my work representing exonerees who had been wrongly convicted, including based on false bitemark, hair comparison, and blood typing evidence. Their bravery and resilience inspired me, and I wanted to work to make sure that our criminal legal system and our scientific institutions never let us down so terribly ever again.

Activities for further discussion

1. Prior to your next gathering, watch a conversation between Keith Harward, whose story is told in Chapter 2, and Peter Neufeld, co-founder of the Innocence Project, hosted by the author: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yJnr3_QbVFI. How does seeing Harward speak about what he endured make you feel about the stakes in criminal cases and forensics? Can society ever truly make it up to exonerees like Harward?

2. Prior to your gathering, watch three short videos featuring Sharia Mayfield, Keith Harward, and Dr. Itiel Dror, as well as the author at the University of California Press book webpage, https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520379336/autopsy-of-a-crime-lab.

3. With members of your discussion group, identify one of the programs recommended by the Innocence Project, https://innocenceproject.org/wrongful-conviction-media/ and watch it separately or as a group. What aspects of Autopsy of a Crime Lab came to mind during your screening? If you found yourself the victim of flawed forensic analysis, where would you choose to start to prove yourself innocent of the crime?

4. Are you one of the more than 26 million people who have submitted their DNA commercial databases to learn more about their ancestry? Popularized by programs like PBS’s Find Your Roots, inexpensive genetic analysis promising clues to one’s family background and medical profile is now widely available, but also largely unregulated. How would you feel if DNA that you or your relatives submitted resulted in criminal prosecutions? What kind of privacy laws—if any—do you feel should be in place for DNA databases? In your conversation, consider the benefits and the drawbacks of this contemporary technology.

5. With your discussion group, consider the some of the forensic failures outlined in Autopsy of a Crime Lab in the larger context of the death penalty. Should death sentences for capital crimes be permitted in cases where exonerating DNA evidence is inadmissible or unattainable? How about life sentences? To what extent are wrongful convictions inevitable in a system administered by human beings? How should wrongful convictions be addressed by our criminal justice system?

6. Have each member of your discussion group write in three sentences or less their essential takeaways from Autopsy of a Crime Lab. Then, have your discussion group share their sentences. How closely do these individual assessments overlap and where do they diverge? If you think of each individual’s three sentences as “expert analysis” of the same material, to what extent does this low-stakes exercise mirror the imprecision of forensic experts offering their own inherently subjective views on evidence?

About the Author

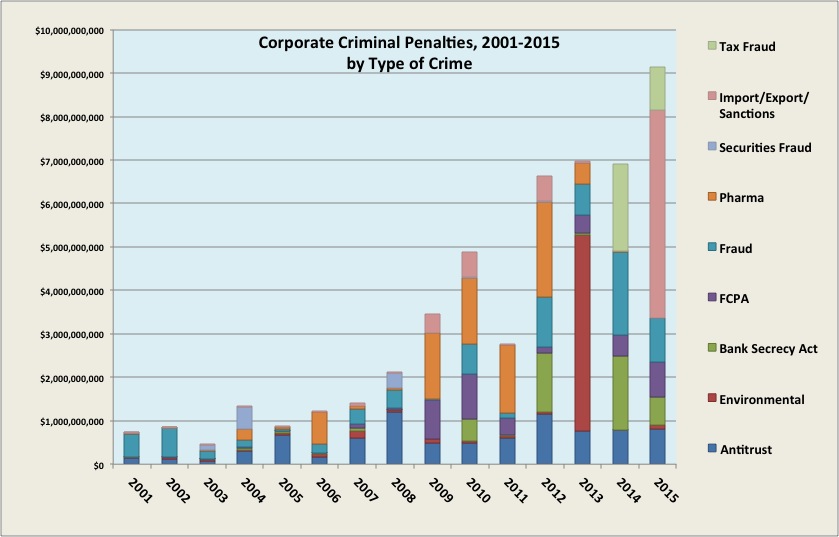

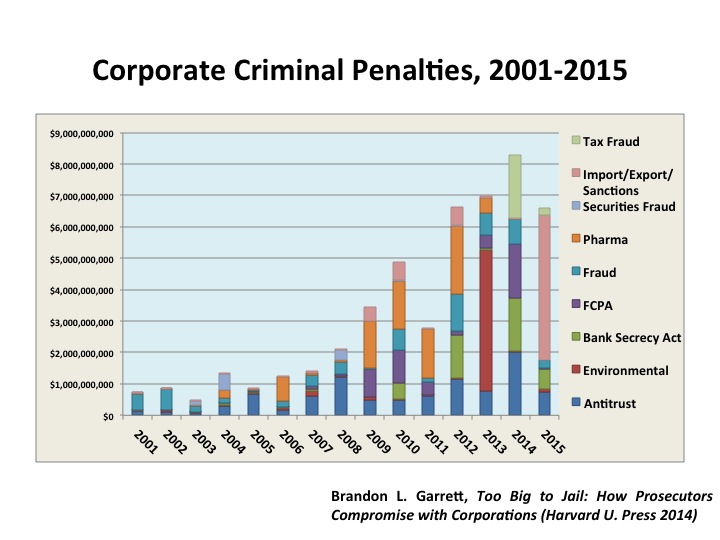

Brandon L. Garrett is the L. Neil Williams, Jr. Professor of Law at Duke University, where he directs the Wilson Center for Science and Justice. His author page is at www.brandonlgarrett.com. His previous books include: Convicting the Innocent: Where Criminal Prosecutions Go Wrong, Too Big to Jail: How Prosecutors Compromise with Corporations, and End of its Rope: How Killing the Death Penalty Can Revive Criminal Justice. He lives in North Carolina with his family.